Below is a recent meditation regarding the beginning of 2016 that I presented to the faculty at Central Seminary.

As my wife Pam will attest, it is difficult for me to walk by a sign that reads “Used Books for Sale.” Like a moth to fire, I am drawn to bumped and bruised volumes found on dusty shelves. So recently I gave into the Siren call of a two-volume work by W. M. Thomson, “twenty five years a missionary of the A.B.C.F.M. in Syria and Palestine,” entitled The Land and the Book; or, Biblical Illustrations Drawn from the Manners and Customs, the Scenes and Scenery of the Holy Land. The copyright date was 1864. This work was so popular in its day that only one other book out sold it, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, by Harriett Beecher Stowe.[1] Almost every literate home of means had a copy of The Land and the Book.

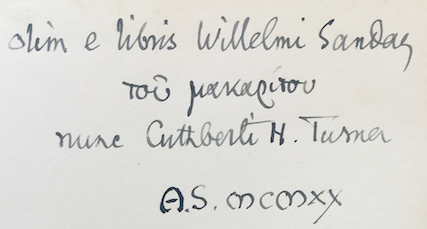

While the volumes interested me from a perspective of one who works in the context of the New Testament and also from an antiquarian angle, one of the features that drew me to these volumes was the inscription on the flyleaf. I am always curious to see if someone has given a book to another and what type of message he or she inscribed. Like a snapshot, the inscription preserves a moment in time when the book was new and the original reader had living eyes on the pages.

In Volume 1, the inscription reads:

To dear Hally

from her affectionate husband

George

Christmas 1864

The brown-inked inscription bore the signs of a careful script delicately written in the mid-nineteenth century cursive style of writing. The pen George dipped into his inkwell had a fine or extra-fine nib; each elegant stroke presents the narrowest of ink line gently slanted to the right. The one flourish the Inscriber allowed himself was on the word “husband” where the last letter “d” tapers off to the left.

Hundreds of unanswered questions could be asked about Hally and George, this couple without any last names who are now gone for over a century and half. Why did George think these volumes about the Holy Land would entertain Hally? Did they hope to travel to that exotic land? Did she ask for the set? Was it a surprise? Were they keeping up with the Jones or the Smith who had these volumes? Did Hally read this book and share bits of it to George over the breakfast table or at dinner? Around a coal fire, did they image tramping around the shores of the Sea of Galilee? What did Hally give George for Christmas in 1864?

In 1864, the Civil War that tore apart North and South had been going on for four years. Did George and Hally have children or family members in the battles? How had their lives been unsettled by the clash of steel and guns, blood and smoke? The war would end in four months, and so would President Lincoln’s life. What were their reactions to the President’s assassination?

Lots of questions. No answers. All that remains are two rather battered volumes that George once presented to Hally at Christmas and this faded inscription. And yet contained within this inscription is a biography of sort. Certainly it is the briefest of biographies one can image, but it is still enough to give us a glimpse.

It is interesting George does not write, “ To my dear wife.” He does not restrict Hally’s role only to the category of wife, which in the 1800s could certainly be narrow and circumscribed for a woman. Rather he calls her by name, the person she is, . . . or was.

But what is even more revealing about Hally and George is summed up in the adjectives used for each. Hally is described as “dear,” and George presents himself as “affectionate.” The ability to check these attributes as qualities of their quotidian lives is beyond our ability to know. But George felt it solid enough to enshrine on the flyleaf of Volume 1 so that 150 years later they are “Dear Hally” and “Affectionate George.”

We have entered the new year of 2016. If you are like me, you are probably wondering what happened to 2015. It seems like it just started and only lasted a week or maybe two at the most. Before long, I will be here again around these tables presenting the faculty devotion for 2017.

This headlong rush into life and its teleological consequences may give one pause on occasions such as the New Year. The writer of James puts it this way, we are “a mist that appears for a little while and then vanishes” (James 4:14b). The start of the New Year might cause us to think about new beginnings, but Hally and George remind us of mists that vanish leaving only faded traces of ink in their wake.

One hundred and fifty years from now, it will be the New Year 2166. Who knows what flotsam and jetsam (or bits and bytes) will remain to mark who we were. But if we had one word, just one, to inscribe upon a flyleaf of a book in order to be remembered 150 later, what would it be?

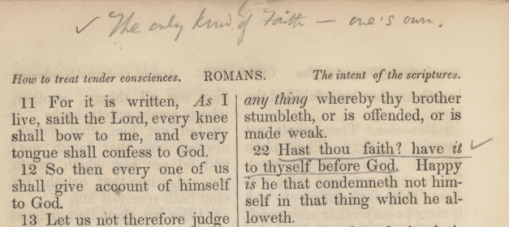

Paul, in his inscription to the Christians at Rome, chose the word slave: “Paul a slave of Jesus Christ called to an apostle.” In the inscription of 3 John, the elder chose the word “beloved” to describe Gaius (v.1), and in Colossians the writer inscribes and describes the whole community with the single word, hagiois: “saints” (Col. 1:2).

Perhaps with all the resolutions made in 2016, all we really need to do is to find that one word with which we wish always to be twinned and to live into it. What is your one word biography for 2016 or 2166?

David M. May

[1] Naomi Shepherd, The Zealous Intruders: Western Rediscovery of Palestine (London: Collins, 1987), p. 90.

In Herman Melville’s book Moby-Dick, the narrator, Ishmael, watched with interest the religious obligation of “Fasting and Humiliation” of his whaling companion Queequeg. While many might have viewed Queequeg’s rituals as strange and even comical, Ishmael did not. He observed in them something universal and says, “Heaven have mercy on us all . . . for we are all somehow dreadfully cracked about the head, and sadly need mending” (Moby-Dick or The Whale [New York: W. W. Norton, 1976], p. 81).

In Herman Melville’s book Moby-Dick, the narrator, Ishmael, watched with interest the religious obligation of “Fasting and Humiliation” of his whaling companion Queequeg. While many might have viewed Queequeg’s rituals as strange and even comical, Ishmael did not. He observed in them something universal and says, “Heaven have mercy on us all . . . for we are all somehow dreadfully cracked about the head, and sadly need mending” (Moby-Dick or The Whale [New York: W. W. Norton, 1976], p. 81). Not every year, but most, I choose a writer and focus upon him or her for the year. Or as Pam would say, “I become obsessed.” I will immerse myself in his or her works and read various biographies. In the past I have focused on writers such as Thomas Hardy, Frederick Buechner, Robertson Davies, John Irving, Walker Percy, or Flannery O’Connor. This is the year of Herman Melville.

Not every year, but most, I choose a writer and focus upon him or her for the year. Or as Pam would say, “I become obsessed.” I will immerse myself in his or her works and read various biographies. In the past I have focused on writers such as Thomas Hardy, Frederick Buechner, Robertson Davies, John Irving, Walker Percy, or Flannery O’Connor. This is the year of Herman Melville.